4 Lessons from Visiting Shanta Foundation in Myanmar

2019 began with a visit to Shanta Foundation, a VVF partner working in Myanmar. In Myanmar, Shanta Foundation’s nationally registered affiliate is named Muditar Foundation, meaning, as their country director tells me “empathetic joyfulness—the idea of experiencing happiness and peace while seeing others happy and prosperous.”

VVF has partnered with Shanta/Muditar since 2017, and we're currently engaged in a 5 year partnership program to support communities in Pauk Township in north-west Myanmar.

Muditar takes an integrated, participatory approach, partnering with villages for 6 years. In that time they help villagers to organize into committees, create a vision for the future and determine their community goals. Then Muditar works with the village to implement programming in education, health care, livelihoods, and leadership.

I was excited to visit Myanmar, but to be being honest my excitement was overshadowed by apprehension due to the political climate. I wasn’t sure what it would mean to travel to a country in the midst of a genocide, and I had mixed feelings about it to say the least. Questions swirled in my brain about the safety, morality, and implications of visiting Myanmar in its current moment—was traveling here without addressing the conflict not only safe, but the right thing to do?

But after connecting with Shanta’s staff and meeting with another Myanmar NGO specifically working to respond to the needs of the Rohingya population, I began to see that my fears were blocking me from seeing another angle. I realized that while Myanmar is in the midst of a horrifying humanitarian crisis, that crisis is not the only thing happening here. There are organizations like Muditar that have managed to work effectively, and it’s not only okay but necessary to support them.

Though not directly working in the conflict zones, Muditar is serving some of the millions of people living in extreme poverty working toward better futures for themselves and their children.

Our trip took us to Shan State and Pauk Township, both in regions outside of Rakhine State where the Rohingya genocide is occurring. And while I can’t say I left reconciling my initial concerns, I certainly left knowing that Shanta Foundation is a force for that better future. Along with that, here are 4 other takeaways from my time there:

1. Great staff inspire great work.

This likely comes as no surprise, but Muditar’s senior staff reminded me of just how powerful it is to have strong leaders guiding the way. We spent significant time with Muditar’s country director, Dr. Sienne Lai Zaw, and two regional managers, Dr. Nye Nye Khaingzar Oo and Mi Mi Kyaw. All three women were sharp, warm, and undeniably dedicated to their work, and getting to know them was a highlight for me.

Pictured below is Mi Mi, regional manager for Pauk (a couple hours drive from the tourist mecca of Bagan and a new region for Muditar as of 2018). Though born in the capital city of Yangon, Mi Mi has lived in and dedicated her work to Pauk since 2012, where she’s found the communities to be honest and enthusiastic. It was clear that all of Muditar’s staff shared this honesty and enthusiasm—Seinne Lai told me that working with the “very passionate staff who share the same vision and commitment even though [they] are from different backgrounds” is part of what inspires her most in her work.

2) There’s magic in a library.

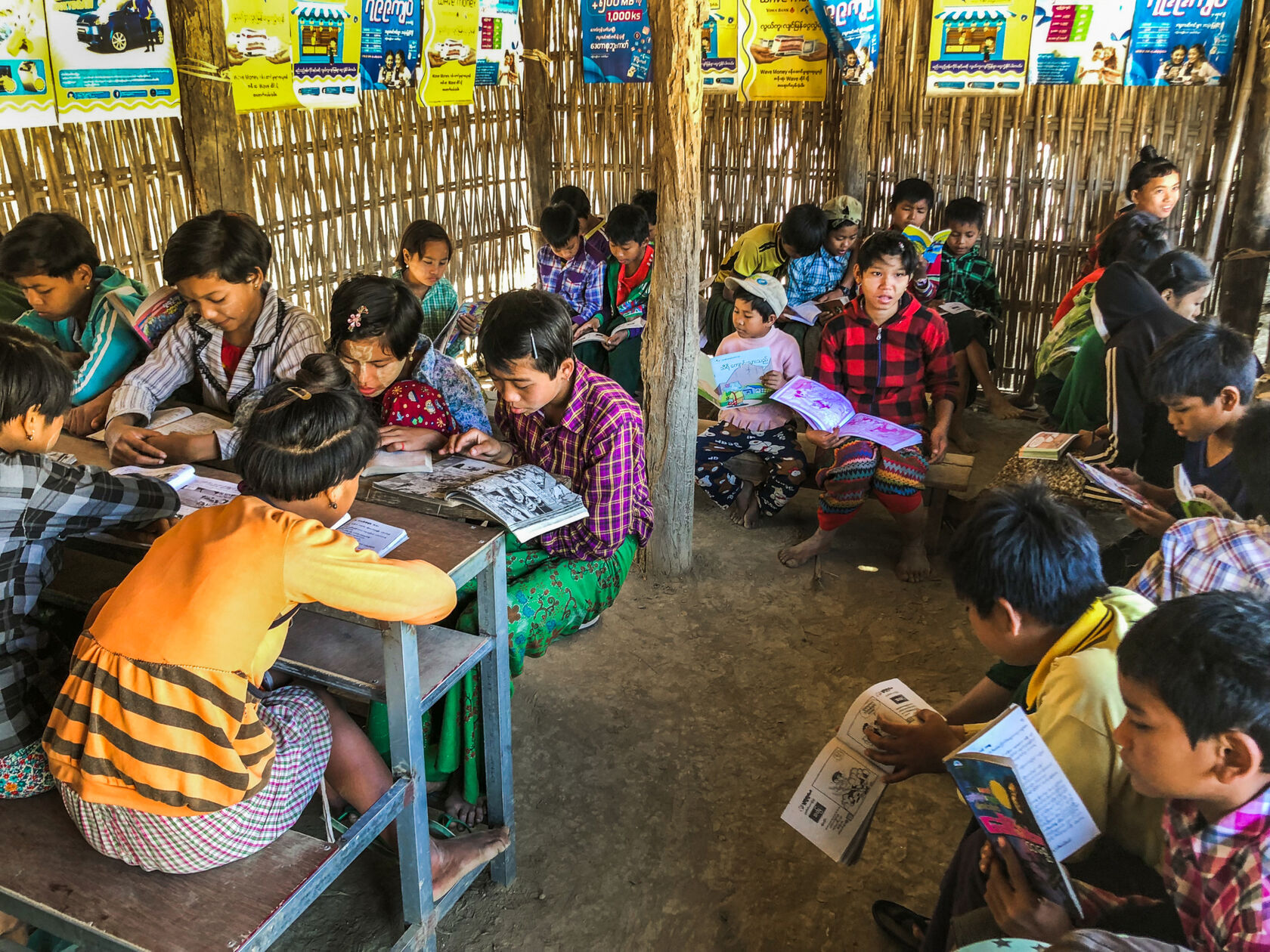

In Muditar’s participatory approach, communities determine which of Muditar’s interventions will be most beneficial, and in nearly all the villages we visited, a school library was a top pick.

When we visited the library in Yay Ka Daw village in Pauk it was packed with kids reading (on a Saturday, I might add) and two teachers—Daw Thinzar Win (pictures below in red) and U Aung Than Maw (pictured below in yellow)—told us the (now somewhat famous) story of how it came to be.

They told us the dream of having a library was alive well before Muditar arrived. In 2017, the teachers initiated a plan to start a vegetable garden on the school compound to make money for a library. That year, teachers and students began planting vegetables, and after a few months sold them in the area.

The students walked through the village advertising “Vegetables for Library,” and by early 2018, teachers were able to buy 50 books. When Muditar arrived 6 months later, the community was thrilled at the chance to expand their library. Now the library is booming and the vegetable garden still brings in income for new books.

The vegetable garden story certainly speaks for itself, but both Aung and Thinzar reiterated the community’s dedication to education, sharing that they both felt determined “to give kids opportunities they didn’t have.”

3) Economic disparities can be difficult to see.

Though there was clearly a lack of resources in the villages I visited, I was surprised by how difficult it was for me to see the income disparities across households. I knew one of Muditar’s primary goals is to increase income so families can put food on the table, but it was hard to see the inequalities during a short visit.

It wasn’t until I returned home and heard from Laurie Meininger, Shanta’s Executive Director, that I realized what I had missed—that a key wealth indicator was in fact hidden in plain view.

Houses in these villages are constructed a level above ground with space beneath to store their annual harvest, and Laurie explained that whether or not families have food stored away can be a good measure of income. So I looked back through my photos and indeed noticed that while some homes were filled with reserved food, others had none, signifying food insecurity. It felt both subtle and obvious, and was a good reminder that inequality is not always evident.

4) The greatest changes can’t be seen from the surface.

I truly feel that the deepest, most profound changes are those that occur inside us—in our hearts and minds—which then manifest outwardly. It seemed that Muditar shares this sentiment, because much of their work emphasizes empowerment, leadership, and self-determination. And while internal change can be difficult to see in a short visit, there were undoubtedly moments when I felt it.

I felt it during our first meeting with a group of community members, when the whole room erupted when asked what they were most looking forward to in the coming years with Muditar.

I felt it when we were told that the gathering area in which we had our meeting had recently been donated by a community member.

And I felt it when the leader of a village we visited said, without having been asked a specific question, “before Muditar, I didn’t know about human rights. Now I see that everyone has the same potential and can speak up.”

It’s hard to define the sort of impact these moments reflect, but if I had to, “empathetic joyfulness” seems to come the closest. I can't thank Muditar and their staff enough for their hospitality and dedication to their work. For more information or to donate to Shanta Foundation, please check out their website.